A Brief Intro to Clean Architecture, Clean DDD, and CQRS

Introduction

In this blog entry I give a primer on Clean Architecture, which is a modern, scalable formal software architecture which is appropriate for modern web applications. Next, I discuss how Domain-Driven Design fits into this picture, and how DDD concepts dovetail nicely into Clean Architecture, producing a methodology called Clean DDD. Finally, I introduce Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS), and describe how it complements and enhances Clean DDD solutions to create software systems that are elegant, robust, scalable, and testable.

As before, here is the link to the demo application.

Clean Architecture

Clean Architecture is a formal architecture which is relatively "modern" in that it is less than ten years old. It evolved over time from several other architectures including Hexagonal Architecture, Ports and Adapters, and Onion Architecture. Clean architecture was formalized by... drum roll... Uncle Bob (here he is again). In this article, Uncle Bob emphasizes five qualities which all of the predecessor architectures and Clean Architecture possess:

- Framework independence: the architecture is decoupled from third party frameworks.

- Testable: the architecture is easy to write unit tests against.

- UI independence: the architecture can be unplugged from the user interface

- Database independence: the architecture is decoupled from the underlying data store.

- External agency independence: the business rules of the architecture are isolated and know nothing about the outside world.

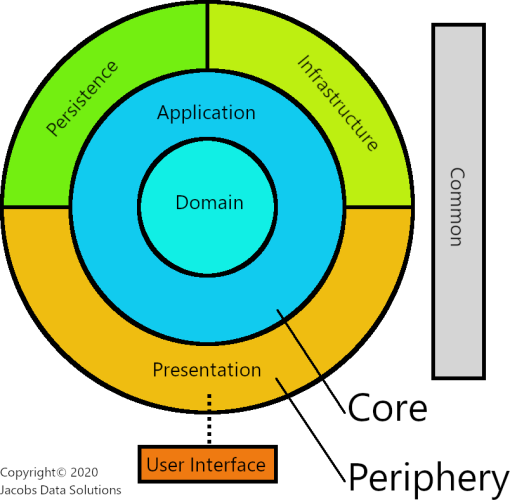

Clean Architecture may be visualized as a series of concentric circles, each representing a different layer of the application. The principle that makes the architecture come together is called the Dependency Rule, as Uncle Bob describes:

"The overriding rule that makes this architecture work is The Dependency Rule. This rule says that source code dependencies can only point inwards. Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle. In particular, the name of something declared in an outer circle must not be mentioned by the code in an inner circle. That includes, functions, classes, variables, or any other named software entity."

This is a great place to start, but I'd like to elaborate on it further. Layers in a Clean Architecture application:

- May never know anything about layers which surround (are outside of) it, just as Uncle Bob states.

- May also never know anything about layers which are adjacent to it.

- Are functionally connected to each other in a live application through Dependency Inversion—i.e. through abstractions (interfaces) which are implemented in outer layers.

The distinguishing feature of Clean Architecture is that the concentric layers which comprise it surround a central core which houses abstractions and business logic. The implementations of those abstractions, along with their external dependencies, get pushed to the outer layers. When describing this layout, I like to use the nomenclature of "periphery" to refer to the outer implementation layers and "core" to refer to the inner layers. Note that this is my naming convention, and you're unlikely to find it used anywhere else at this time.

Again, I'd like to emphasize how we are explicitly using the Dependency Inversion principle to ensure that inside layers (pure logic and abstractions) NEVER have any knowledge of outside layers (implementations). Inside layers work with the abstractions that are defined within those layers, and the actual implementation logic exists in the outside layers. To reiterate: The Dependency Inversion principle states that details depend upon abstractions; abstractions do not depend upon details. So, we are drawing a distinction between what is essential (the core) vs. what is a detail (the periphery). Everything comes together in the finished solution using dependency injection, typically via an inversion of control container.

Clean Domain-Driven Design

My interpretation of Clean DDD

Clean Domain-Driven Design represents the next logical step in the development of software architectures. This approach is derived from Uncle Bob's original architecture but conceptually slightly different. It is the same in that it uses the same concentric layer approach at a high level, however domain-driven design is utilized to architect out the inner core. Furthermore, the DDD impetus toward domain separation into different bounded contexts also informs this design, as those bounded contexts now become guides for horizontal separation of each layer of the stack. This is a true, modern, heliocentric model to build and deliver complex business applications. There is not unanimous agreement on how to go about this, so I am presenting my interpretation. This is influenced heavily by Jason Taylor's architecture, which in turn seems to be inspired by the architecture presented in the Microsoft E-book, .NET Microservices: Architecture for Containerized .NET Applications, specifically the chapter on DDD and CQRS.

Core Layers

Domain Layer

The Domain layer is the centermost layer in the core. This layer is built out using DDD principles, and nothing in it has any knowledge of anything outside it. For the most part, dependency injection is not used here, though perhaps a rare exception could be made for the event dispatcher implementation. Domain services and other business logic within the Domain layer don't even really need to be behind interfaces since that logic is less likely to change over time and there's less of a need for polymorphism. In areas of the domain where it does make sense to use interfaces, such as using the Strategy pattern to encapsulate different pieces of business logic, go ahead and use them; otherwise, just inject the domain services directly into your classes that need them.

Application Layer

The Application layer is extremely important, as it is basically the "glue" that binds the Domain layer to the outer layers. It is almost like an intermediary layer. The Application layer declares interfaces and other abstractions which stand for infrastructure, persistence, and presentation components. The actual implementations for these components are NOT declared in this layer but are provided to Application components via dependency injection.

This layer is also responsible for orchestration: it implements high-level logic which manipulates domain objects and kicks off domain workflows. In this way, it does not contain any first-class business logic itself, but rather organizes that logic via calls to/from the Domain layer. It may coordinate tasks and delegate work to the domain, but it does not contain business rules or maintain business state.

The Application layer likewise performs persistence operations using the injected persistence interfaces. This is where the Repository pattern comes into play, or CQRS (explained below). It passes Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) back up the stack to the Presentation layer as a result of different orchestration operations. Likewise, it also communicates with the operating system and other external resources using injected infrastructure interfaces.

Periphery Layers

Persistence Layer

The Persistence layer contains implementations for the persistence facade interfaces declared in the Application layer. It also contains specialized persistence model (data access) classes which may or may not be mirror images of the database tables (especially if you are using an Object Relational Mapper, a.k.a. ORM) or which may represent projections of database queries. This is where all the hard logic resides that does the actual reads/writes to and from a database. Without getting too deep into the weeds, I will state that you can use an ORM, micro-ORM or straight database access (ADO.NET) to implement these details. It doesn't matter. Hybrid approaches are also okay and can be beneficial. The demo application shows such an approach, and I'll discuss more later.

Infrastructure Layer

The Infrastructure layer contains implementations for the infrastructure interfaces declared in the Application layer. There isn't much to say here, because it is what you'd expect: it encapsulates logic to communicate with operating system, external APIs, etc. Implementation details of communicating with an external message queue go in here, along with services that communicate with any other outside agency.

Presentation Layer

The Presentation layer is an API layer that brings together all the Application layer components and injects them with the proper implementations (typically using an IOC container). In my interpretation, this layer is NOT the user interface (UI), but rather presents a facade which the UI communicates with. I'll discuss this more in the next blog entry. In a web application, the Presentation layer is an MVC application and it communicates with the UI using a web protocol such as REST, GraphQL, or web sockets. Going forward, when I talk about MVC controllers, know that I am always referring to them as Presentation layer components.

Now, there's something you need to be aware of. Some of the sources I've studied regard the web API as the Application layer of the system. In other words, the Application layer and Presentation layer seem to be one and the same. I strongly disagree with this. The Application layer is its own animal, and you should always be able to decouple it from the presentation logic, should the need arise.

Data is passed back and forth between the Presentation layer and the UI using view model objects, which are the native entities of this layer. So, for instance, it is very common to declare view model classes in the Presentation layer and use a specialized tool to automatically generate TypeScript classes which are directly consumable in your UI. ASP.NET automatically serializes the view model classes into JSON when they are passed back from controller methods, and the UI deserializes them as TypeScript classes which can be consumed by a single-page application (SPA), for instance. There's a nuance here that I'll explain in the next blog entry, because my actual implementation of this architecture doesn't follow this exactly. View model objects often map conceptually to different screens or interactions in the UI. They are tailored to the client application.

User Interface

The User Interface is the absolute highest conceptual layer in this architecture. This is the code that users directly interact with. Some examples might be SPAs like Angular or React, which run inside a user's web browser, or a desktop application built using Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF). Some sources lump this in with the Presentation layer, but I think it's important to keep it separate, at least in web applications. If architected well, your system should be capable of having the UI removed and replaced with a different one without too much effort.

Common layer

The Common layer is a library or set of libraries for cross-cutting concerns such as logging, text manipulation, date/time arithmetic, configuration etc. which are global to the entire system. Components and interfaces in the Common layer may be used in ANY layer of the stack (except for the UI, which will likely be entirely disconnected and in the case of web apps, running entirely in the user's browser). I want to make clear that this is NOT the same thing as the Shared Kernel, which I covered in the previous blog entry on Domain-Driven Design. The difference is that the Shared Kernel is a common library for the Domain layer, which contains common base classes, domain entities, value objects, etc. which are shared across bounded contexts. The Common layer contains implementation details for components and functionality that are general enough that they can be used anywhere in the application. On that note, there should be absolutely no business logic or anything having to do with the domain in here.

Once again, beware of the One Ring of Power anti-pattern. Be diligent to keep this layer from ballooning out of control. When in doubt as to whether something belongs in the Common layer, think to yourself, is this component something that I could reuse in entirely different software systems, or even put into a reusable toolkit on NuGet? If the answer is 'No' then you really need to consider whether it's a cross-cutting concern, or if it belongs in another part of the system.

A Primer on CQRS

CQRS stands for Command/Query Responsibility Segregation, and it's a wonderful thing. This is an architectural design pattern which allows higher-level layers, such as the Presentation layer, to communicate through the stack to other layers, such as the Application layer—e.g. controllers inside the Presentation layer will invoke commands and queries which are executed by Application layer components. CQRS dovetails beautifully with Clean Domain-Driven Design because it is a behavioral pattern: Clean DDD is the what, CQRS is the how.

Before I dig deeper, I want to make clear that you don't NEED to use CQRS to implement Clean Architecture or Clean DDD solutions, but why wouldn't you use it? For sake of argument, an alternative approach could be to encapsulate your orchestration logic inside Application layer services, which are injected directly into your controllers. Everything is tidy and respects the Dependency Inversion principle. However, you've forfeited the benefits that CQRS provides, in that it abstracts away the communication process itself between components across layer boundaries. If that sounds slightly confusing, relax, I'll explain more below.

CQRS was developed by Greg Young in 2010. It is based upon the Command Query Separation (CQS) principle, which was introduced by Bertrand Meyer in the 1980s. The CQS principle states:

- High-level operations which query a system's data should not produce any side effects—i.e. modify state. These are called Queries. Queries return data to the Presentation layer via DTOs.

- High-level operations which modify the system should not return data. These should produce side effects, modify the state of the system, and then complete. These are called Commands.

- In practice, commands may return a small piece of metadata, such as the ID of a newly created entity, but that's it. Commands may also return an ack/nack response.

- Another result of the command execution may be an error condition, in which case the command should throw an exception.

CQS on its Own

CQS can be implemented directly in a Clean DDD solution. To do this, you would typically break apart your controller methods into commands/queries (i.e. write/read) operations, and never violate the separation between the two. The intent is to create a task-based interface, which processes behavior rather than just saving data or performing other CRUD operations. Pay attention here: this is where CQS and CQRS intersect with DDD—the operations themselves will often be named after business processes using the ubiquitous language of the bounded context you are working in. Note that this simple, elegant design also promotes the Single Responsibility principle, because each operation is more cohesive and corresponds better to UI operations. This facilitates a development process which approaches User Experience (UX)-Driven Development.

The opposite of CQS is an anti-pattern which I've unfortunately seen far too often: zero separation between commands and queries. In this non-design, there is no real way to understand what the side effects are for a given operation because there is always some Rube Goldberg logic operating under the hood. This is very common in legacy applications that are over 10 years old but a lot of career developers who should know better still build solutions this way. Another common anti-pattern is to expose CRUD operations on the controllers (web API) and then the business logic gets dispersed throughout the application, such as in the UI itself or worse, in the database inside stored procedures. This produces labyrinthine, brittle solutions that violate the Open/Closed principle to a ridiculously extreme extent, and which break every time you touch them.

CQRS is CQS+

Command Query Responsibility Segregation, what is it? CQRS is CQS on steroids. CQRS takes commands and queries and turns them into first-class objects. A solution using a CQS, tasked-based interface can be easily refactored into CQRS because the logical separation is already there. The big difference between the two patterns is that in CQS commands/queries are methods; in CQRS, models. The distinction here is important. By treating operations as models, you are introducing an unbelievable degree of scalability into your application. This is not unlike what the .NET team did way back in the day with the introduction of the Task Parallel Library (TPL): they took the onerous process of developing asynchronous control flow in applications and abstracted all of that into first-class objects which can be handled independently of the code which depends upon them. Remember what I said in blog entry 4 about thinking abstractly? This is a prime example. Another byproduct of using CQRS that shouldn't be overlooked is that commands/queries themselves become serializable data contracts.

Here are few obvious benefits to using CQRS:

- Scalability: there are usually far more read operations against a system than writes (remember our friend, the Pareto principle?). Under CQRS queries can be broken apart into their own stack and scaled independently of commands.

- Performance: you can build in optimizations that aren't possible in a tightly coupled model.

- Simplicity: Vladimir Khorikov calls this the most significant benefit and I agree with him. You pay a small amount of complexity in the beginning by using this in your architecture, but you earn it back in spades down the road as the solution grows to meet business demands. Over time, it is much more maintainable and better able to manage complexity.

How it Works

At a high level, commands/queries are instantiated in the Presentation layer (inside controller actions) and communicated to the Application layer, which then performs the business orchestration logic and executes the high-level task you're interested in.

One approach is to have the command/query parameters and the logic which handles them all in the same object. That object gets injected into each controller using dependency injection or created using a factory of some sort. An Execute() method is invoked on the command/query object and the result is retrieved. I don't like this.

A better way to implement CQRS is to separate commands/queries from their handlers and utilize an in-process messaging service to dispatch the command/query objects to their respective handlers. This is an exemplary case of the Gang of Four Mediator pattern in the wild. There are enormous benefits to doing this, but two obvious ones are:

- It simplifies your code because you don't have to write boilerplate to wire up commands/queries to their respective handlers.

- You have created a high-level task execution pipeline in your application, within which you can inject cross-cutting concerns such as error-handling, caching, logging, validation, retry, and more. This is huge.

How you go about implementing this is up to you. On the one hand, you can roll your own in-process messaging service (not recommended) OR you can utilize a pre-built messaging framework, such as MediatR (I recommend you do this). An alternative approach to using a messaging pipeline may be using something like the Decorator pattern to "attach" additional behaviors onto your commands/queries. I personally think this is smelly and don't recommend it, which is why I built the demo solution using MediatR.

Commands

CQRS commands are always named in the present imperative tense—e.g. RegisterEmployeeCommand. Commands alter system state and return simple ack/nack or metadata responses, or they throw an exception. They differ from domain events in that commands can be rejected; events cannot. Commands often interact with the Domain layer via the Application layer. This is important because the Domain layer contains all the business logic and is responsible for keeping the system in a consistent state. The properties which comprise the commands should be structured as close to 3rd normal form as possible [Greg Young, CQRS Documents]. If you're interested in the difference between 1NF/2NF/3NF, this Quora post does a good job of explaining it. Lastly, commands often need to be idempotent. A good example for this might be if you have a command which charges a customer's credit card—the command should be rerunnable and shouldn't double or triple charge the customer.

Queries

CQRS queries are also named in the present tense and typically start with "Get"—e.g. GetEmployeeListQuery. Queries do not alter system state, they just return data, usually in the form of a data transfer object. The properties on the returned DTO are structured close to 1st normal form, as the data will probably be coming back from a denormalized database query, and the structure of the returned DTO will often match the user's screen or some canonical model that can be used by any client.

In his original specification, and most of the experts I've studied agree with this, Greg Young states that most of the time queries should bypass the Domain layer. Let's unpack this further. Why would we want to pass straight through from Application layer to the Presentation layer? First, the data model is more reliable than user input and assumed to always be consistent, so there shouldn't be a need to do validation coming out of the database. Secondly, queries don't change state, so there's no use for business domain logic which does that manipulation. Thirdly, reads (queries) will be occurring more frequently than writes (commands) in a system, so they need to be fast and efficient. Going along with this last point, many of the experts recommend not even using an ORM on the query side. The demo solution shows just this approach. In sum, queries which go through the Domain layer ARE allowed, but that is the exception to the rule.

Additional Considerations for Both Commands and Queries

- As stated in the section on CQS, both commands and queries should be named using the ubiquitous language and represent task-based operations, rather than CRUD.

- The suffixes "Command" and "Query" are optional, so use your own discretion. Just make sure that your naming conventions are intuitive and consistent.

- "Optional" properties are a design smell and could be indicative that your task-based operations are not cohesive enough.

- Do not call commands/queries from other commands/queries. This is a big-time smell if you do. If you have a need to retrieve data from the database in the logic for a command, then you should simply query the database directly using an ORM or some other approach. Note that this is a prime example in which certain principles must be violated in order to uphold other ones. In this case, we are violating DRY so that we avoid dangerously coupling the two sides of our stack together and turning the whole thing into an unmaintainable pile of garbage. If you find yourself debating between loose coupling and DRY, loose coupling wins.

Final Thoughts About CQRS

I reserve the right to modify this or any of my blog entries, so it's likely that I'll add more here at some future point. Before I wrap up the discussion on CQRS, I'd like to mention that, ideally, the solution (software) should fit the problem like a glove on a hand. For this reason, a properly implemented CQRS solution may display a marked degree of asymmetry. If you have Asperger's a keen attention to detail like I do, this might strike you as wrong. However, nature isn't always perfectly symmetric, and neither are human inventions. As stated in the section on CQS, in a typical software system users perform far more read operations than write operations. It's the Pareto principle again, hiding behind the curtain like the Wizard of Oz. The completed system should reflect this.

The Holy Grail? Clean DDD + CQRS

Everything was leading up to this point. Going forward I will be using this as the primary architectural approach for web application development, and it's what I've used in the demo application. Just to reiterate, the high-level architecture is based upon Clean Architecture principles, with a clear conceptual separation between concentric layers of the system.

- The innermost layer of the system, the center of the core, is the Domain layer, which has been built using DDD principles. The Application layer surrounds the Domain layer and is part of the core. The Application layer contains business orchestration logic inside commands/queries, interfaces that are implemented by periphery layers, and model classes which are used to communicate with outside layers.

- The Presentation, Infrastructure and Persistence layers sit along the periphery, and have no explicit knowledge of each other. The Presentation layer essentially is a web API that some arbitrary UI, like Angular, can communicate with.

- CQRS is the essential ingredient which allows the layers to elegantly communicate down the stack. This is what ties everything together. Dependency injection likewise is critical for wiring the components together while still observing the Dependency Inversion principle. An IOC container helps with this.

Once again, there is no silver bullet, so what are some of the pros and cons?

Pros

- If we build our abstractions well, then this architecture is independent of external frameworks, user interfaces, databases, etc. In other words, it is flexible. Frameworks and external resources can be plugged/unplugged with much less effort.

- The solution is vastly more testable.

- It is much more scalable.

- It is easier to manage necessary complexity, that is, complexity introduced as a result of trying to solve the actual business problem.

- The solution can be worked on and maintained by different teams, without stepping on each others' toes. Clean DDD lends itself well to Agile processes.

- It is much simpler to add new features, including complicated ones, allowing the developers to pivot more quickly and release faster. As the system grows over time, the difficulty in adding new features remains constant and relatively small. This is in sharp contrast to many legacy systems I've worked on, in which adding new features becomes prohibitively more costly and difficult over time until finally the whole thing goes over the Cliff of Maintainability and must be scrapped.

- If the solution is properly broken apart along bounded context lines, it becomes easy to convert pieces of it into microservices.

- All the above points are pointing to the same conclusion, which is that overall the system will have much greater longevity, and a much lower cost over the long-term.

Cons

- This is a sophisticated architecture which requires a firm understanding of quality software principles, such as SOLID, decoupling at an architectural level, etc. Any team implementing such a solution will almost certainly require an expert (YOU) to drive the solution and keep it from evolving the wrong way and accumulating technical debt.

- Clean DDD requires more ceremony than just writing a plain monolithic 3-layered application comprised of a single project.

- There is added up-front complexity to support the architecture, which may necessitate using additional toolkits to minimize the pain, such as AutoMapper and MediatR.

- This architecture is generally ill-suited to simple CRUD applications and could over-complicate such solutions. Conversely, it could be argued that CRUD is unnatural, goes against human nature, and forces the business teams to change their behavior to accommodate the software system, rather than the other way around. But that's a different discussion...

- Change (as in changing one's mind) is difficult. Trying to get buy-in from management and other team members might require a good deal of convincing.

- In sum, there is a greater up-front cost to this approach. You need to decide if it's worth it in your situation.

Advanced Topics

Since this is an introductory blog series, I'm not going to get too much into these topics. I'm just mentioning them, so you know they're out there.

First off, the separation of commands from queries allows you to split the stack all the way down to the database. In extreme architectures there may be a database which is only used for commands and one or more separate databases that are used only for reads. Further, the read databases can be denormalized, which can vastly improve performance and scalability. I have no intention of implementing this architecture in the demo application at this time.

CQRS taken to its extreme logical conclusion results in an architectural pattern called Event Sourcing, which essentially means that state data is NOT stored in the command database, but rather a series of events which have mutated the data from some basic, initialized state. By "replaying" the events, a snapshot of the data can be obtained which allows you to get the state of the data from any point in time. This snapshot can be synchronized over time to the read databases through eventual consistency, or some other replication pattern. Such an approach might be appropriate for certain advanced applications, such as financial applications. For our purposes, I'm fine with having a single database and not trying to implement Event Sourcing. The price you pay for implementing such advanced architectural patterns is significantly increased complexity. Lastly, most of the experts I've studied agree that CQRS can provide huge benefits without using Event Sourcing. This is another area in which I'd advise you to exercise caution, as these kinds of advanced patterns are not for the faint of heart.

Conclusion

In this blog entry I introduced Clean Architecture, which is a first-class architecture which has developed over time from several other architectural approaches and was first formalized by Uncle Bob. Then I discussed how Domain-Driven Design fits together with Clean Architecture to produce Clean DDD, an architectural approach which combines the methodology and business-centricity of DDD with the logical separation of Clean Architecture to produce applications which are elegant and easier to convert into microservices. Finally, I introduced CQRS, a behavioral architectural pattern which augments Clean DDD, resulting in everything from improved performance to easier testing and better scalability.

Experts / Authorities / Resources

Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob)

- Clean Coder

- The Clean Architecture (Classic Blog Posting)

Cesar de la Torre, Bill Wagner, Mike Rousos

Greg Young

- CQRS Documents (Classic Whitepaper)

Vladimir Khorikov

Dino Esposito

Matthew Renze

Jason Taylor

Jimmy Bogard

- Jimmy Bogard - Home

- LosTechies.com

- MediatR (GitHub)

This is entry #7 in the Foundational Concepts Series

If you want to view or submit comments you must accept the cookie consent.